The Great Depression of the 1930s, the impact on the economy, the marginalization of indigenous peoples, Afro-descendants, and labor exploitation are just a few of the events that have shaped the historical framework that will affect the development of Guayasamín’s work. On the other hand, the fights for the working class and native peoples’ re-independence were taking shape in Ecuador’s intellectual environment, as they were in the rest of Latin America, and they would be mirrored in literature and the arts. The Second World War’s horrors, the Mexican Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and finally the danger of nuclear annihilation during the so-called Cold War all made headlines on a global scale.

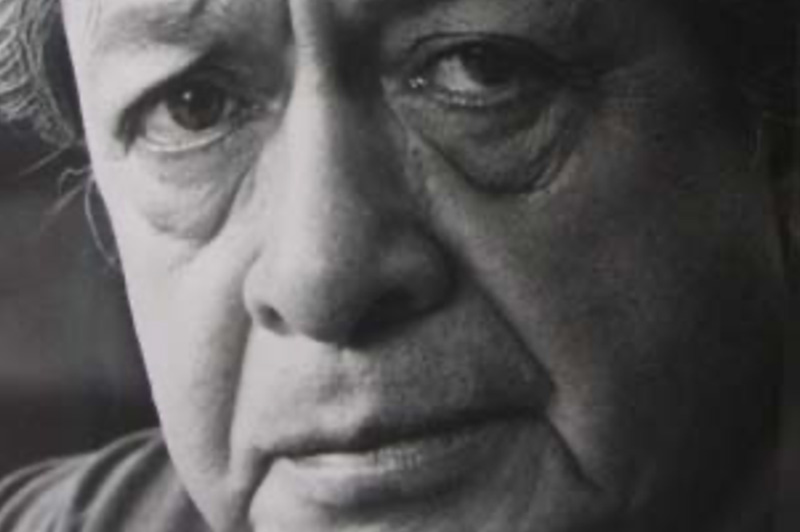

The Ecuadorian artist will draw inspiration from his youth and the historical context surrounding the 20th century. His upbringing was marked by poverty and disrespect for his indigenous heritage. These components will infiltrate his artistic work, transforming it into a protest against injustice and the predatory exploitation of the most vulnerable people.

Guayasamín earned his degree in painting and sculpture at the National School of Fine Arts in 1940. In 1942 he won the prize at the Mariano Aguilera National Salon. The Ecuadorian artist’s dedication to socialist philosophy, indigenism, and the expressionist avant-garde is visible in his work. Due to the social condemnation of his paintings, the debut exhibition of the painter from Quito was surrounded by a significant amount of controversy. Impressed with Guayasamín ‘s paintings, Nelson Rockefeller, the man in charge of Inter-American affairs in the United States, buys five of them. Guayasamín visits the United States to showcase his work. Then he returns to Mexico to work as José Clemente Orozco’s assistant, and meets Diego Rivera.

He traveled from Mexico to Patagonia in 1945, experiencing firsthand the horrible poverty that pervaded most of Latin America. The series Huaycañan (1952–1953), named after the Quechua word for “The way of Tears,” was the outcome of this journey and the encouragement of the intellectual Benjamin Carrión (founder of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana). The series was composed of 103 pieces. In Huaycañan, Guayasamín depicts the anthropology of the marginalization of indigenous, Afro-descendant, and mestizo communities, criticizing the excruciating pain and inhumanity endured by the most defenseless inhabitants of the continent while simultaneously glorifying their efforts and hopes. In this first series, the Ecuadorian painter creates a synthesis between the influence of Mexican muralism and his artistic personality, evolving towards a more avant-garde drawing of lines, colors, textures, and compositions, without abandoning expressionist figuration.

The Quiteño artist got numerous international awards after winning first place in painting at the III Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte in 1956 and the Bienal de San Pablo in 1957.

The Age of Wrath is the title of Guayasamín’s second television series, which he started around 1960. In it, he discusses the atrocities of human violence that occurred in the 20th century, including the barbarism of Nazi concentration camps, the massacres of the Spanish Civil War, the dictatorships that eroded freedom in Latin America, the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the invasion of Playa Giron in Cuba, among others. In addition, the Ecuadorian painter outlines the forms not only with the black lines of his brush but also with scratches that reveal the white base of the preparation of the painting. The hands of the master from Quito paint forms that become more rough and disembodied. His brushstrokes and, above all, the precise gestures of the spatula provide the pictorial matter forming strata that cover the tortured bone structure of his human figures with a skin of anguish.

Sharp lines and colorful surfaces that are layered on the brisk beat of the master’s spatula are used to shape the faces and hands, which are becoming increasingly dominant in the tortured anatomy depicted by the Quiteño artist. We can infer the brightness of a soul drenched in emotions from the black sockets of his characters’ eyes. To represent the synthesis between the sensitivity that moves the artist’s guts and the subject matter to be portrayed, the color palette is a crucial component of Guayasamín’s visual language. The color of ochre and soils, black, icy and metallic blue, blood red typically accompanied by deep green, and the uncompromising hardness of gray are characteristics of the Age of Wrath. We see the artist from Quito at his most mature in The Age of Wrath.

The Guayasamín Foundation was founded in 1976, and its establishment will aid in preserving the artist’s legacy for Ecuador’s cultural legacy. Along with his works, the Quito-based painter donates collections of ancient, colonial, and modern artwork. As a tribute to the memory of his mother, who was always his rock, the Ecuadorian artist created his series Mientras viva siempre te recuerdo, also known as the Age of Tenderness, in the 1980s. The loving figures of the mother and her kid, the series’ central characters, seem to arise from the composition of lines and shapes, in contrast to The Age of Anger. The hands embrace and caress the faces as they come together endearingly in the forefront, drawing smiles and innocence. The medium and typically square format of the canvases, along with the color scheme of ochre, yellows, and blues, create a dynamic balance that communicates closeness and care. Although this series is scattered, the Guayasamín Foundation houses a substantial sample.

Share:

The Chapel of Man was a project, declared a priority project by UNESCO, started in 1996 by a Quiteño-based artist and is regarded as a love song to America. It acknowledges and exalts the Mayan-Quiché, Aztec, Aymara, and Inca cultures by recalling their cosmology, symbolism, sacred texts, flora, and wildlife. Guayasamín also discusses the violent uprooting of Afro-descendants from their land into slavery and the anguish of mothers looking for their children who vanished under the dictatorship, among other bloody events of conquest, and despotism. Examples of such events include the death of the original inhabitants in the infamous Potosí hill mines and their enslavement. Early works by the Ecuadorian painter, a few pieces from the Huaycañán series, pieces from the Age of Anger series, and a few examples of the Age of Tenderness series may all be found in The Chapel of Man. All of these images come together to create a hymn that builds in hope for the triumph of human rights from the clamorous scream of the earth’s dispossessed to a crescendo. The Chapel of Man is a revelation of the spirit of the Ecuadorian painter who calls out, “Keep a light on, I will always come back.” It is the culmination and legacy of the artist.

Large-scale portraits, murals, flower still lifes, landscapes, watercolors, engravings, sculptures, and jewelry designs are all works by Guayasamín. The artist, who was born in Quito, held more than 200 significant shows all around the world. The Quiteño painter also depicted many of the most well-known individuals in the spheres of politics, art, literature, music, actors, thinkers, and even some members of the European nobility, in addition to his loved ones.

There aren’t many painters in America as potent as this non-transferable Ecuadorian, the poet Pablo Neruda once said of his friend Guayasamín. The Quito-born painter, who holds a prominent position in Ecuador’s second half of the 20th-century cultural scene, was the most notable artist of his generation. His political stance and aesthetic conceit are evident in each of his plastic motions. Guayasamín stated that the purpose of his paintings was to hurt, itch, and strike at the hearts of viewers. To demonstrate what Man can do to Man.

According to Ecuadorian author Jorge Enrique Adoum, the great murals in Guayasamín vibrate with echoes of Michelangelo’s tortured spirit in His Last Judgment, the horrifying scenes in Los Desastres de la Guerra, the drama in Goya’s Los Fusilamientos del 3 de Mayo, and the explosive avant-gardism in Picasso’s Guernica. One of the greatest artists of the 20th century, along with the Mexican Rufino Tamayo and the Brazilian Candido Portinari. Guayasamín chose for his painting the palpable and visible reality of his continent, the tears on the faces of the dispossessed of the earth, and the traces of the infamy that war and injustice left on the margins of the world, while Lam painted the American jungle with its spell of vegetable demons and Matta reaffirmed in Europe the reality of the imagination and dream of Latin America.

Guayasamín’s contribution consists in depicting the drama of human suffering, the condemnation of social injustice, and the fight for human rights and turning them into the raw materials of his art through his unique vision of history, challenging the viewer and putting what he typically wants to avoid in front of him. The Ecuadorian maestro adopted the figurative expressionism language and gave it his forms, textures, and colors by filtering it through his technique and sensibility. He was able to evoke at the same time the ancestral roots of the continent, the roughness of the avant-garde, and the wisdom of the great masters of Western art, constituting his work in coherent bodies. Beyond a remnant of the ideological-political Manichaeism that was prevalent at the time, the outcome of this synthesis is a solid artistic work that addresses universal themes that probe the viewer’s very existence: pain, violence, death, outrage against injustice, motherhood, tenderness, and love make the master Guayasamín’s work transcend time and space.